#010: An Invitation to a Multicultural Metatribe

Lessons from a Liminal Foremother, Gloria Anzaldúa, and a Response to Joe Lightfoot's Mapping of the “Liminal Web”

After reading Joe Lightfoot’s piece "The Liminal Web: Mapping An Emergent Subculture Of Sensemakers, Meta-Theorists & Systems Poets” I was moved to add to (not critique) his image of liminal space. My intention is to bring in voices from other realms in hopes that we of the Liminal Web can realize a fuller potential of this time between worlds for collective emergence.

In particular, the current conversation has some of the inherent limitations of an early more homogenous group of people gathering around a passion, and perhaps due to this misses a tremendous source of original wisdom in the works of early explorers.

The skills and learnings of these early explorers could well take the Liminal Web to a broader and deeper understanding of what is possible by revealing the shoulders on which we stand and the gifts our forebearers offer.

My Liminal Story

Twelve years ago I came across a word that changed me forever. It captured my experience as someone who had been forced to navigate two divergent cultures (Japanese and American) as well as unique intersections of experience and disciplines (tech startups, art, design thinking, depth psychology, mindfulness, neuroscience, trauma theory, leadership coaching).

That word was liminal.

In 2011 I published my Master’s thesis on the search for wholeness as a biracial woman which led me to the idea of Liminal Identity. This was the inception of my work of not only helping people of mixed heritage find wholeness in contradicting identities, but also helping people navigate challenging situations of cultural difference in their personal lives and at work.

So you can imagine my delight when I stumbled upon Joe Lightfoot's article. He draws a circle around areas of the web where I have been spending my time and points out the emerging liminal-oriented metatribe. When I first read this I felt an immediate sense of "liminal belonging."

And yet there was something missing. Where were the voices of early explorers of the liminal? And where were the voices of those who wrote from within their experience of the liminal – not just about the experience?

So I took up Lightfoot's invitation to "compare notes" by both adding to the Liminal Web conversation and offering an invitation to members of this particular multicultural metatribe.

What is the “Liminal Web” and the metatribe?

The “Liminal Web” as described by Joe Lightfoot is, “a collection of thinkers, writers, theorists, podcasters, videographers and community builders who share a high crossover in their collection of perspectives on the world.”

More concisely, per Tyler Alterman’s definition of the metatribe on Twitter, this is a group of people wherein the “members tend to be multi-hyphenate: artist-scientist; dancer-entrepreneur; programmer-monk. Their work often synthesizes multiple disciplines at once.” They “tend to be at the center of a Venn diagram with many circles, often dwelling at the edge of many subcultures at once, acting as nodes between them.”

What is missing in Lightfoot’s Liminal Web?

Lightfoot does make an effort to list many of the shadows and biases of the Liminal Web. He points out, for example, that the space is very homogenous in that it is made up of primarily WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic) white men. We could easily extend that list to include heterosexual and cisgender.

I am not saying this to shame nor even be morally critical of this fact. It is human nature to connect with those similar to ourselves. As a mixed-race Asian-American female who grew up in a WEIRD country, when I have joined these spaces I have felt welcome. (I also realize that what I will be highlighting is U.S.-centric and I not only invite, I would love(!), to hear from people outside WEIRD countries about how what I’m sharing here resonates or does not resonate for you.)

Demographic liminal identity

There is, however, a cost to the shallowness of our pool of perspectives and experiences. Lightfoot and Alterman’s definitions of this liminal space suffer from this very issue. When describing the nature of the Liminal Web or metatribe they focus on interests and beliefs.

I would like to offer that a more full and complete definition of liminal or metatribe members must also include people—liminals—who not only tend to be multifaceted in their interests and disciplines, but are themselves embodiments of Venn diagrams via their demographic identities: race (mixed-race, Black-Asian), ancestry/ethnicity (Afro-Cuban, Asian-American), gender (non-binary, trans), and sexuality (queer) to name a few. [1][2]

Perhaps in part because of this oversight, the other essential feature absent in the mapping of the Liminal Web is any reference to the early explorers of the liminal experience. Due to their life experience being the impetus for exploration, many were of course mixed-race, multicultural, queer or women of color in America and often marginalized.

By including and building on these early lessons we can create a stronger and more whole view of what is possible in liminal spaces, while also cultivating spaces that are more heterogeneous and thus more alive and generative.

And so, my dear metatribe, I would like to introduce you to the work of Gloria Anzaldúa.

An early foremother of Liminality in Culture & Identity

Image of Gloria Anzaldúa by Annie F. Valva.

Gloria Anzaldúa was a visionary, award-winning writer, storyteller, poet-philosopher who wrote from inside her experience of traveling within the cracks of identity as a sixth generation child of farmworkers, Chicana, American, feminist, academic, and activist.

During the years from 1981 until 2004 when she passed away, Anzaldúa wrote and edited numerous pieces, sharing her evolving understanding of the lived experience of living between worlds. Her best known work is Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza and the other is the award-winning This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color (1981) with Cherríe Moraga. She inspired many including AnaLouise Keating, María Lugones, and Mariana Ortega to name a few.

By looking at the unfoldment of the work of Anzaldúa as she wrestled with her identity at the intersection of numerous conflicting differences, we can learn some valuable lessons about how to cultivate more inclusive, transformational, multiracial and multicultural liminal spaces.

Five Liminal Lessons for the multicultural metatribe

The following are lessons for better navigating our disorienting liminal moment that I have gathered from Anzaldúa and the work she inspired. I also name the places where I see members of the Liminal Web expressing some of these lessons.

1) Engage from an embodied, somatically-aware stance

Lightfoot mentions in his article that one of the "shadows and blindspots" of the current Liminal Web is how "overly intellectual and analytical" the people of this space can be. One of the reasons I appreciate the writings of Gloria Anzaldúa is that she applied a phenomenological approach to the exploration of liminality.

Anzaldúa’s approach is embodied, relational and experiential. Even her style of writing—using breaks in sentences for side personal commentary and shifting back and forth between English and Spanish—captured her experience of being in a liminal, threshold space and displaced the reader from normative forms of English-centered communication.

Bridges span liminal (threshold) spaces between worlds, spaces I call nepantla, a Náhuatl word meaning tierra entre medio. (Reader, p. 243)

Anzaldúa draws intuitively on the page in a way that inspires a sensory experience. In Geographies of Selves—Reimagining Identity: Nos/Otras (Us/Other), las Nepantleras, and the New Tribalism Anzaldúa writes about our bodies and identity:

Our bodies are geographies of selves made up of diverse, bordering and overlapping “countries.” …. As our bodies interact with internal and external, real and virtual, past and present environments, people, and objects around us, we weave (tejemos), and are woven into, our identities. Identity, as consciously and unconsciously created, is always in process—self interacting with different communities and worlds. Identity is relational….Identity is multilayered, stretching in all directions, from past to present, vertically and horizontally, chronologically and spatially. (Light in the Dark, p. 69)

Our Nervous System

Anzaldúa evokes our bodies, and the way they both internally and externally engage with our surroundings. When facilitating groups I’ve noticed how unaware people are (facilitators included) of how activated their nervous systems are [3]. When we are very activated and unaware we can lose cognitive and relational capabilities making communicating less effective. This is what I mean by dysregulation.

Glimpses in the Liminal Web

This embodied, somatically-aware stance is expressed by Bonnitta Roy, one of the thinkers named by Lightfoot as a member of the Liminal Web, through her Pop-Up School.

The Invitation

In addition to the intellectual and analytical, we need more embodied, relational, and experiential skills and experiences in the metatribe.

What is your somatic experience of Nos/Otras (Us/Other)? What sensations do you notice in your body as you pause and feel into this? Are you able to feel into it, or is this way of experiencing new to you? If you are just starting out, slow down for a moment and start by noticing the arrival of physical tension, perhaps in your belly, chest, or neck.

When you rest your attention on the slash between “Nos” and “Otras” what do you notice? Again, what sensations arise? Do subtle movements come? Do you lean back, or lean forward? Does your sense of personal space feel larger or smaller? What emotions arise?

What possibilities for new ways of relating might now be available to you?

2) Listen deeply with vulnerability and openness

Many of us know that listening is important. Few know how to listen deeply—so deeply that we are open to being changed.

Anzaldúa grappled with radical inclusivity during the creation of the book This Bridge Called My Back. Some of the contributors wanted to limit the collection to women of color. Anzadúa completely understood the reason behind this desire—women of color felt that “Anglo-American” women were tokenizing, stereotyping, ignoring them and treating them as less than. “Do you ever really read the work of black women? Did you ever read my words, or did you merely finger through them for quotations?” wrote Audre Lorde, a Black, lesbian, activist poet wrote to a white feminist. (Keating, Transformation Now!, p.53)

The women of color feminists were asking to be deeply listened to by white feminists. At the same time, even among the white feminists those who were Jewish and/or working-class felt similarly ignored by Christian, middle-class white feminists.

Despite the many painful divisions, Anzaldzúa invited everyone to listen to each other with vulnerability and an open mind. This was a radical ask of the community at the time and still is today.

When we listen with vulnerability and openness, listening is multidirectional. We allow ourselves to be changed and even wounded. Keating writes that listening in this way can even be dangerous. In Transformation Now! she writes,

Peeling back our defensive barriers, we expose ourselves (our identities, our beliefs, our worldviews, and sometimes even our secret desires) to change. By so doing, we can acquire new, sometimes shocking, insights about ourselves and others. (p.53)

When we listen deeply, vulnerably, and with openness we allow our preconceptions to drop, we put aside our own needs and desires for the moment, and we allow the full consciousness of the Other to join us. As we do this, a more complete and true complexity is allowed to reveal itself. The complexity of the Other, ourselves and the relevant systems and structures between and around us can suddenly become visible. This larger, richer picture includes the views of all present and, where they meet, grows larger still. By letting go of our positions and preconceptions we allow them to drift up into this bigger shared view. There we can see possibilities that were hidden and together emerge what is new and more appropriate to the reality at hand.

Wonderfully, in addition to seeing a fuller picture, we are also using co-regulation to calm each others’ nervous systems and increase our cognitive capacity. When we perceive a threat to ourselves, a belief, or an identity we hold dear (more about mitigating this later) we can enter a heightened state of “fight ready” activation [3]. One of the impacts of this state is that our prefrontal cortex (our “thinking” brain) shuts down and makes dialog even more difficult.

Recent research into Polyvagal Theory reveals that when we relax our nervous systems, such as we must do to facilitate this kind of listening, it can be seen on our face and heard in our voice. The other person picks up these subliminal cues, their nervous system begins to co-regulate with ours, and our prefrontal cortices come back online.

By listening deeply through relaxing both our nervous systems and our rigid positions, we physiologically and psychologically have the capacity to fully engage with reality and draw fresh insights.

Glimpses in the Liminal Web

Listening deeply with vulnerability and openness can be found in Daniel Brooks’ Authentic Relating, John Vervaeke’s dia-logos, and Guy Sengstock’s Circling practice. Zen teacher Diane Musho Hamilton brings this radical openness to working with difference in her book Compassionate Conversations.

The Invitation

During your next small argument try relaxing into the tension, perhaps by allowing a long, slow exhale.

What is true about what the other is saying?

How might you let their words impact you?

Notice what sensations arise as you let their words impact you.

3) Travel between worlds without colonizing them

Building on the previous lesson of listening deeply we can also be more mindful of how we travel to others’ worlds.

When our demographic identities are in alignment with the normative culture they are essentially invisible. When the world around you looks like you, you don't notice that aspects of your identity exist as unique traits. In the U.S., for example, there are many contexts where a white person rarely has to think of themselves as, “white,” while a Black or Latinx person is reminded regularly of their racial identity through it’s easily noted difference from the norm.

One unconsciously becomes skilled at tracking times when they are "in" their culture's world and when they are "outside" of it. This often leads to a need for, and manifestation of, code-switching (Parody with Key and Peele). María Lugones, an Argentine feminist philosopher, activist, and professor of comparative literature and of women's studies, explains this kind of “World-Travelling” or “travel” as the ontological “shift from being one person to being a different person.” The shift may not be intentional or, again, even conscious.

Lugones offers a warning for those of a dominant culture: that they can “travel” in a way that expresses itself as an attempt to “conquer the other ‘world’” (p. 16) (i.e. colonize it). I would offer that this happens when people subconsciously impose their understanding of their world onto another world, thus “killing” it—and losing the opportunity for the emergence of something new in the liminal space that could have been formed where the differences met.

We can enact world-traveling just by being in conversation. “We can occupy the same space, but given our different social identities, we will be in that space in many different ways depending on the dominant norms, practices, and relations of power at work.” (Ortega, In-Between, p.93)

How do we “travel” without colonizing? Through what Lugones calls “playfulness.” To “travel” to different “worlds” with playfulness means (p. 17) to have:

Openness to surprise

Openness to being a fool

Openness to self-construction or reconstruction

Openness to construction or reconstruction of the “worlds” we inhabit

Glimpses in the Liminal Web

I found this approach alluded to by Tyson Yunkaporta, senior lecturer in Indigenous Knowledges at Deakin University in Melbourne and a member of the Apalech Clan and a carver of traditional tools and weapons (as well as a member of the Liminal Web). In this New York Times article about his book Sand Talk, Yunkaporta responds, “I constantly have to explain the Indigenous point of view. But what if it was the other way? What if it was turning the Indigenous point of view on the world and describing what we see?”

The Invitation

When you engage with someone from a different culture do you leave having learned something about the other—or do you leave having one of your own essential paradigms reshaped? Upon returning to your world does it look changed—changed in a way that reframes how you see and engage with yourself and your world?

In order to be a more multicultural metatribe we need to become more skilled at traveling to each other’s worlds with “playfulness” so that we can not only know each other, but know “what it is to be ourselves in their eyes.” (Lugones, World-Travelling, p. 17)

Think about a recent interaction with someone significantly different from yourself.

Which of your existing models might you have been trying to fit them or their views or their world into?

What might you learn by starting from their view of you?

What body sensations or emotions arise as you consider this?

4) Cultivate antifragility of the self

In order to listen deeply and let our worldviews be radically transformed we need a sense of self that is antifragile.

Though the above-listed Anzaldúa-inspired writers don’t use Nassim Nicholas Taleb’s term antifragile, they do advocate for cultivating a self that has antifragile attributes. Antifragility is “a property of systems that increase in capability to thrive as a result of stressors, shocks, volatility, noise, mistakes, faults, attacks, or failures.” [emphasis mine] It is not simply “not fragile,” but rather the opposite of fragile. Rather than striving for resilience or robustness—which keeps our level of capacity fixed—antifragility has us grow in capacity as we are met with stressors.

In order to have a more antifragile self, we need to cultivate a self that can grow from ruptures in relationships and collisions between our identities and the world.

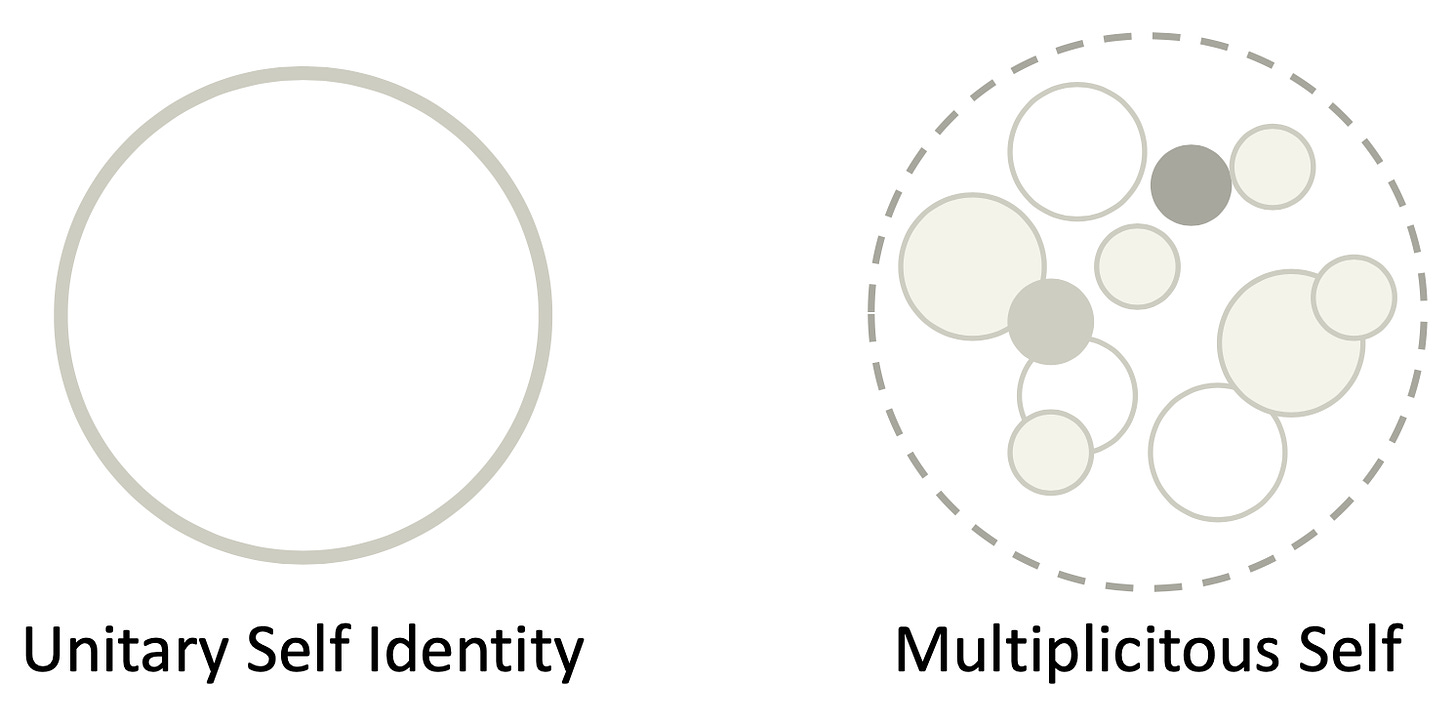

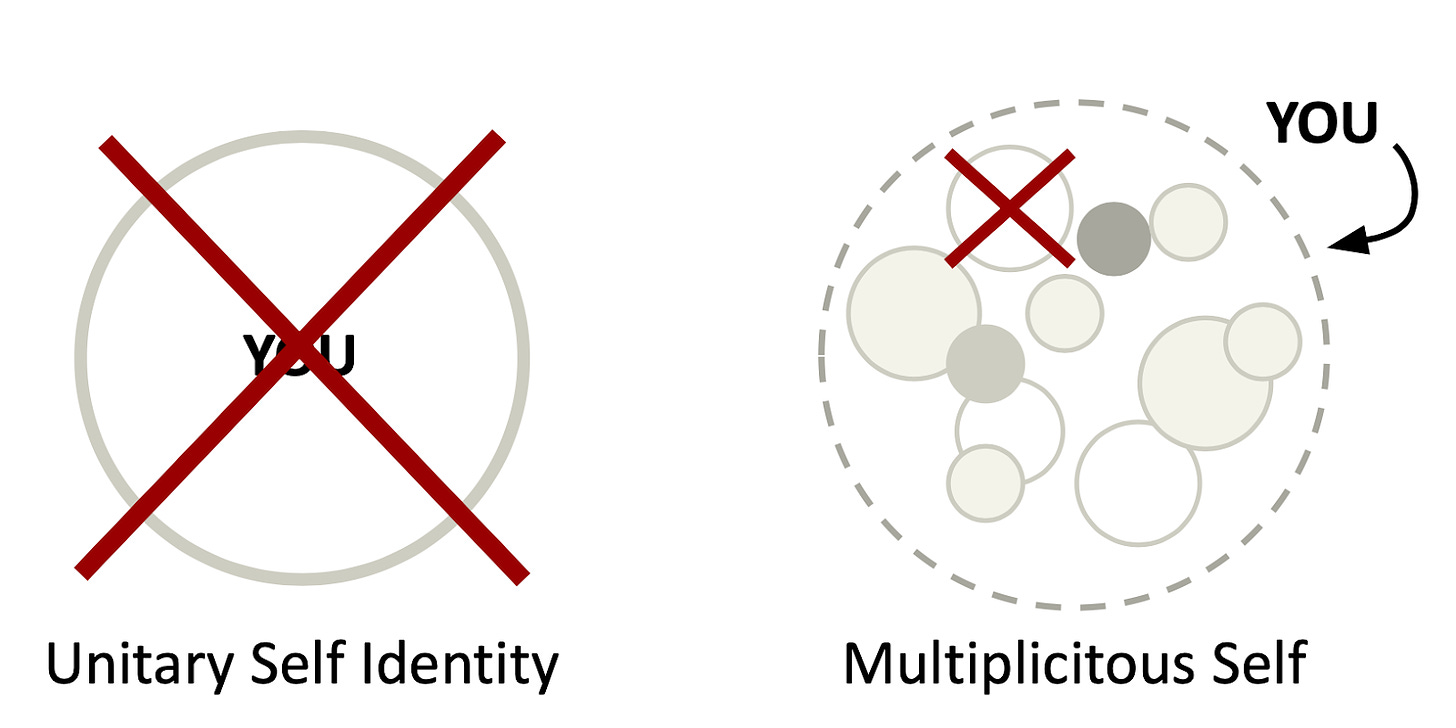

We need to shift from a unitary, static, fragile self to a self that is multiplicitous and fluid.

When a single aspect of who we are feels as though it is all of who we are there is no room to hold the tension of opposites. We will immediately be polarized by contact with the Other and our nervous system will dysregulate. However, when only “a part of us” gets activated by the conflict of meeting the Other, the greater whole of us can hold the tension. [4]

In her book In-Between: Latina Feminist Phenomenology, Multiplicity, and the Self, Mariana Ortega makes clear that Anzaldúa and Lugones don’t experience “themselves as moving from one identity to another that is more accurate or truer…they describe their experience as one in which there is a sense of ambiguity, liminality, multiplicity, and even contradiction.” (p. 180)

Anzaldúa demonstrates this when explaining the mestiza:

The new mestiza copes by developing a tolerance for contradictions, a tolerance for ambiguity. She learns to be an Indian in Mexican culture, to be a Mexican from an Anglo point of view. She learns to juggle cultures. She has a plural personality, she operates in a pluralistic mode—nothing is thrust out, the good the bad and the ugly, nothing rejected, nothing abandoned. Not only does she sustain contradictions, she turns the ambivalence into something else. (1987, 79) [my emphasis]

By acknowledging the self as multiple (i.e. full of contradictions) we can make space for more complexity in seemingly oppositional conversations. Our selves hold our perspectives and by state-shifting from a single self to a multiplicitous self (and thus hold differing perspectives simultaneously) we can see more of the whole picture. We can also feel more steady in those conversations by having more ground on which to stand.

Glimpses in the Liminal Web

This idea of antifragility of self can be felt in both Ayishat Akanbi and Zen teacher Diane Musho Hamilton’s ways of being in this Rebel Wisdom interview.

The Invitation

When in oppositional conversations it can feel like the ground we stand on, and count on, is threatened. If we are “wrong” and this vanishes, where will we stand? It can feel destabilizing and unnerving. When we know, however, that there is a vast terrain to stand on, dialoguing can be less fraught and allow room for new perspectives and understanding. We can then practice antifragility—our space to stand growing larger each time we face a new challenge to our understanding.

Write down as many of your identities as you can. Start with your interests and demographics. (Example: chess player, soccer player, reader, male, Hispanic, Yoruban, cosplayer)

Draw a Venn diagram with three circles.

Select two demographic identities (gender, sex, race, ethnicity, nationality, dis/ability, religion) and one interest-based identity and fill in the Venn diagram. (Example: ADHD, Afro-Caribbean, programmer)

Now look at each circle in turn. Pause and feel your body take the shape of each identity. Do you feel expanded or contracted? Tight or relaxed? Open or closed?

Look at the center of the Venn diagram where all three meet. Feel into the shape your body takes to express that intersection. Notice what thoughts, feelings, and sensations arise. How grounded do you feel?

How might this exercise inform the way you engage the world?

5) Practice a non-oppositional and non-binary approach

All of the above lessons can only be enacted from a non-oppositional and non-binary stance.

My own response to oppressive behaviors was, historically, to react oppositionally. I got angry, my heart raced, my blood pressure rose, and I wanted to fight. I defined myself by what I opposed—anti-racism, anti-sexism, anti-oppression. When teaching classes on culture and identity, I witnessed students often equate discussions with battlefields. They want to be taught skills to arm themselves for combat.

After sitting in these oppositional spaces for over a decade, I became disillusioned by this approach's efficacy for real change. If we are working with a dichotomous framework of one person being “right” and the other being “wrong”, then participants will be focused on claiming the “right” position (See position-based negotiation). When that happens, there is very little listening or learning. I just see others, including myself, dig their heels in deeper to prove themselves “right.”

Instead of oppositional dialogue, I support what Keating calls “transformational dialogues—conversations with the potential for conversion.” (Transformation Now!, p. 18) In this type of dialogue rather than seeing opposition, we can see the “interrelatedness of positions and propositions that transcends the dualistic essentialism of persuasive discourse” (Mark McPhail, Zen p.80)

There isn’t anything inherently wrong with oppositional dialogue. I agree with M. Jacqui Alexander,

[o]ur oppositional politic has been necessary, but it will never sustain us; while it may give us some temporary gains ... it can never ultimately feed that deep place within us: that space of the erotic, that space of the soul, that space of the Divine. (Keating, "I'm a citizen of the universe", 2008)

For us to shift to something truly new we need to make space for that newness to emerge. Anzaldúa reminds us of what psychologist Carl Jung wrote about the transcendent function, that “if you hold opposites long enough without taking sides a new identity emerges.” (p. 548) [5]

Glimpses in the Liminal Web

This non-oppositional approach can be seen in Diane Musho Hamilton’s approach to working with conflict as seen in her book Compassionate Conversations: How to Speak and Listen from the Heart. Elements of this approach also appear to be part of the overall platform presented by Game B.

The Invitation

Think back to a conversation where you found yourself arguing for one of two opposing perspectives. Walk through the conversation in your mind and, as you do, pause midway.

What does oppositional energy feel like in your body? What emotions arise? What images arise?

What might you say that captures the fullness of the tension rather than picking a side?

If you weren’t focused on trying to be right, what might the conversation look like?

Invitation: Let us become las nepantleras together

For Anzaldúa ‘las nepantleras’ are “threshold people, those who move within and among multiple worlds and use their movement in the service of transformation.”

I believe the metatribe is made up of many nepantleras.

Las nepantleras walk through fire on many bridges…by turning the flames into a radiance of awareness that orients, guides, and supports those who cannot cross over on their own. Inhabiting the liminal spaces where change occurs, las nepantleras encourage others to ground themselves to their own bodies and connect to their own internal resources, thus empowering themselves. (p. 571)

Some of you might have heard the call to become a nepantlera. I certainly have.

In order for us to dance at the thresholds of difference we need to cultivate a flexible, antifragile multiplicitous sense of self—a self that is embodied, relational and can feel and express from within experience beyond mere conceptual understanding.

I hope this brief introduction to Anzaldúa, Keating, Lugones, and Ortega’s writing has inspired you as much as it inspired me. There is, of course, much more to be learned from these and other early pioneers in the exploration of the liminal.

For links to my source material please see the resources and footnotes below.

Where to find me

www.mindfuldiversity.com

angellaokawa.substack.com

“All that you touch

You Change.All that you Change,

Changes you.”

Footnotes

This expanded definition was inspired by Ruth Cobb Hill’s paper (2010) on Liminal Identity where she defined liminal as “a person living on the threshold between two worlds and two racial identities.”

Note: I am taking Alterman's use of the word "subcultures" to refer to interest-based social cultures rather than ethnic, regional or economic cultures.

I define activation as when our nervous system goes into a reflexive protective state in response to sensations and our environment. (See Polyvagal Theory, Neuroception)

The multiplicitous self:

Houses numerous dynamic worlds that are constantly changing. (Selves are selving)

The dynamic worlds (selves) are in relationship with the world as well as with each other.

There can be marginalized selves (female, BIPOC) and dominant selves (neurotypical, able-bodied, cisgender)

The focus of selfhood is not on any particular self at a given time, but on holding the pluralism of selves.

Jungian Thomas Singer wrote about the Transcendent Function in regards to President Barack Obama’s biraciality. Read his piece here.

References

Anzaldúa Gloria, & Keating, A. L. (2010). The Gloria Anzaldúa reader. Duke University Press.

Anzaldúa Gloria, & Keating, A. L. (2013). This bridge we call home radical visions for transformation. Taylor and Francis.

Anzaldúa Gloria. (2012). Borderlands: La frontera: The New Mestiza. Aunt Lute Books.

Anzaldúa, G., & Keating, A. L. (2015). Light in the dark luz en lo oscuro: Rewriting identity, spirituality, reality. Duke University Press.

Moraga Cherríe, & Anzaldúa Gloria. (2015). This bridge called my back: Writings by radical women of color (Fourth). SUNY Press.

Hill, R. C. (2010). Liminal identity to wholeness. Jung Journal: Culture & Psyche, 4, 16-30.

Keating, A. (2013). Transformation now!: Toward a post-oppositional politics of change. University of Illinois Press.

Lugones, María (1987). “Playfulness, "World"-Travelling, and Loving Perception.” Hypatia, Vol. 2, No. 2 (Summer, 1987), pp. 3-19

Okawa (Enders), Angella (2011). Finding wholeness: Understanding liminality through my experience as a biracial woman (Master’s thesis). Pacifica Graduate Institute, Carpinteria, CA.

Ortega, M. (2016). In-Between worlds: Latina feminist phenomenology, multiplicity, and the self. SUNY Press.